Richard Chappell recently had a lovely post asking people to disagree with him. I obliged by expressing my misgivings about what he calls beneficentrism, “The view that promoting the general welfare is deeply important, and should be amongst one’s central life projects.” I argued instead for

a relatively strong partialist account, in which one is obligated to promote the welfare of those one is directly engaged with – co-workers, family, friends, fellow organization members, maybe neighbours – but going beyond that is supererogatory. (Beyond that circle there are harms that one is obligated not to cause, but harm and benefit are not symmetrical.)

I liked Chappell’s main response, which seemed to deemphasize obligation, and I didn’t find much to object to:

we would do well, morally speaking, to dedicate at least 10% of our efforts or resources to doing as much good as possible (via permissible means). Whether this is obligatory or supererogatory doesn’t much interest me. The more important normative claim is just that this is clearly a very worthwhile thing to do, very much better than largely ignoring utilitarian considerations.

But he also linked to a backgrounder on obligation, and there I found much more to disagree with. I agree with Chappell’s most basic point in the backgrounder: that it is “unfortunate” that “Delineating the boundary between ‘permissible’ and ‘impermissible’ actions… has traditionally been seen as the central question of ethics”. But I disagree entirely with his reasoning for this view.

I take particular issue with this paragraph:

It encourages moral laxity. We should not be aiming to act in a minimally permissible way. Calling a good act “supererogatory” (above and beyond the call of duty) has an air of dismissal about it. When asking “Do I have to do this?” the answer may indeed be “No,” but that wasn’t the best question to begin with.

From my perspective, if you think there’s something wrong with “aiming to act in a minimally permissible way”, you’re too close to a view that does focus on the permissible. Rather, you should indeed make sure that your actions are minimally permissible – that you’re not doing anything blameworthy, anything wrong – so that you can get on with all the rest of your life, the areas beyond obligation, justice, and what I think most people would consider morality.

Consequentialists and deontologists generally agree that the subject matter of ethics should be moral actions (often moral decisions). We virtue ethicists (a motley crew including Buddhists, Stoics, Epicureans, Nietzscheans and others as well as Aristotelians) generally disagree with this. We are concerned with what it is to live a good life – in ways that include our feelings as well as our actions, but also in ways that go beyond morality per se. Bernard Williams rightly redirects our attention from “What should one do?” to “How should one live?”, and in so doing, from morality to ethics. The questions “Should I eat tomatoes or pancakes?”, or “Should I attend McGill or the University of Toronto?”, are important questions for a good life – for our flourishing – but I don’t think it makes sense to call them moral questions, because they don’t have to do with blame, with justice, with obligations to others. Morality is one sphere of life, and deontic concepts like obligation are helpful to demarcate it from the rest. Chappell and I agree that ethics shouldn’t be primarily about obligation, but I think that that’s precisely the reason concepts of obligation are important – in order to put obligation in its limited place.

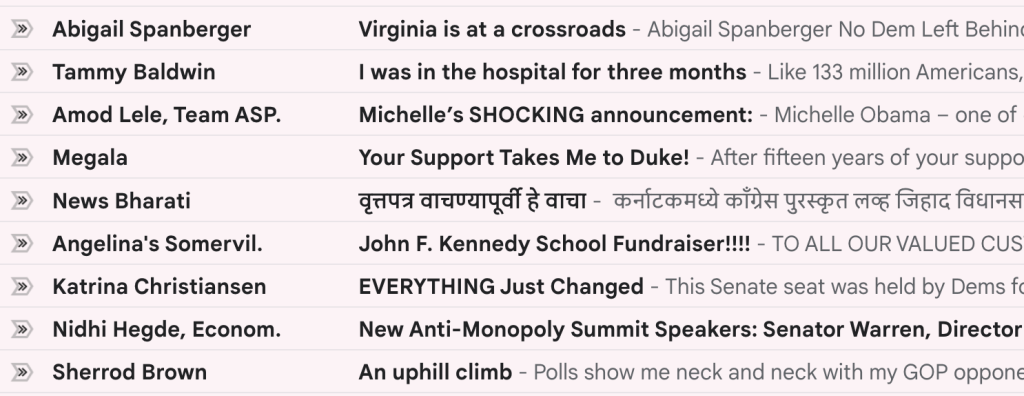

This all is important because we live in a world suffused with guilt! Every day we are bombarded with emails from charities and political organizations telling us to contribute more of our income, not to mention the panhandlers we pass on the street. Anti-racist activists claim that we are always so suffused with implicit bias that we must continually hunt it down within our souls. American employees are often expected to work on evenings and weekends and vacation days – a mechanism enforced by many means, but a key one among them being guilt. (“You really should get that report in before Monday morning.”) Families impose on us similarly. Actually doing the things they ask – giving lots of money to the charities, working 60-hour weeks – rarely results in fewer demands being made. And this guilt economy reinforces patriarchy, because women are typically expected to feel such obligations more than men are. The world keeps telling us we’re not doing enough; it’s up to us to figure out when we are.

It is essential to living well to be able to say: you have done enough. Among the reasons we need to be moral as part of a good life is in order to have a clear conscience – and from it, self-respect. On Robin Dillon’s feminist concept of self-respect, “the self-respecting person has a keen appreciation of her own worth” – an appreciation we lose when we are feeling guilty about how much more there is to do. Even if there is more to be done in the future, it is important to know that you have satisfied your obligations to this date, you are good enough, you have done what is required, what you need to do. Anything more is great, but you don’t have to do it and you can breathe easy, no matter how many moral entrepreneurs are trying to call you “morally lax”. We should have an air of dismissal toward them; it’s vital to.

Once one has done what one is required to do, there are many good things one can do with the rest of one’s life – creating art for connoisseurs, taking care of one’s family, meditating, promoting the general welfare – and bad things, like taking heroin, scrolling for hours on Reddit, or getting angry at news reports. Perhaps the proportion of this remainder that one should typically devote to the general welfare should be 10%; perhaps it should be even higher. But the criterion for determining that must have to do with one’s flourishing, in a way informed by one’s own cares and aims; it should not be about “laxity”.

The use of “moral laxity” implies that Chappell believes something is wrong (and probably even blameworthy) with someone who doesn’t do the “very worthwhile” thing, something wrong in a specifically moral sense. That is, something is wrong with this person that isn’t wrong with someone who smokes a pack a day or rides a motorbike without a helmet. All of this indicates to me that, in the moral (rather than legal) senses of “supererogatory” or “permissible”, he doesn’t actually believe such an action to be permissible. To put it in the simplest language, he believes that acting in that way is not okay. And that’s what I have a problem with.

Living a good life means, among other things, not just making others happy but being happy oneself. And one is not going to be happy if one is always haunted by the fear of being “morally lax”. The idea of supererogatory acts is important precisely so that we are able to live with ourselves: to be able to say that, in fact, we have done enough – amid all the people who tell us we haven’t.

A couple of thoughts came to mind as I was reading this post.

The first was the relevance of the Mahāyāna emphasis on altruistic intention, which Sonam Rinchen expressed clearly in a passage in his book The Bodhisattva Vow (Snow Lion Publications, 2000) that I quoted once before in a comment on Amod’s post “The Buddhist oxygen mask” (2021):

The central concept in this Mahāyāna view, as I understand it, is universal beneficent intention, not duty/obligation. Because the intention is universal, it’s impossible to fully realize it in our actions: we can’t really give everything to everyone. So the intention never causes guilt because there is no expectation of realization. We just do our best within our capacity: we keep trying to do better without overdoing it and without ever giving up the intention to give everything to everyone.

This practice requires a lot of reasoning and experimenting to figure out what is within our capacity; it can be helpful to express this capacity as a percentage of our time and other resources. But this practice is also a gradual practice of psychological transformation/development: our deep psychological schemas that shape our intention can be restructured/transformed. There is no emphasis on this transformation in Amod’s post or in the post by Richard Y. Chappell to which it responds, but such transformation is central to Mahāyāna Buddhism. (In addition to the many Buddhist texts about this transformation, a couple of interesting recent articles that relate it to Western moral theory are: Stephen E. Harris, “Demandingness, well-being and the bodhisattva path”, Sophia, 54(2), 2015, 201–216; and Alex Rajczi, “Moral transformation and duties of beneficence”, Sophia, 58(3), 2019, 455–473.)

Richard Y. Chappell, in his comment on the Substack copy of Amod’s post, said:

That passage from Chappell is close to the Mahāyāna view that I’ve been trying to voice here. The Mahāyāna view is definitely not a moral minimalism, but it’s radically different from the Western roots of Chappell’s view in that the Mahāyāna view posits a maximalism of intention (not of action) that emphasizes the importance of our own intention and how it can be transformed: it’s a psychological developmental “beneficentrism” (Chappell’s term) that focuses on transforming the mental intention of the moral agent toward each being in all beings and all beings in each being.

In the Mahāyāna view, I doubt that developing universal beneficent intention is properly classed as “supererogatory”. As Chappell said, in his comment on the Substack copy of Amod’s post:

Likewise, in the Mahāyāna view, it’s a kind of mistake not to develop universal beneficent intention, which is part of a whole psychological transformation that is likely to improve our lives in many ways, including our ability to uphold the most minimal ordinary norms/precepts.

The second thought that came to mind is that this post by Amod is very focused on the individual, but there’s also a communal aspect to all of this: our psychological and moral development is enhanced by participating in communities that are intentional about such development.

Thanks, Nathan. I wrote about Harris’s article earlier here: https://loveofallwisdom.com/blog/2015/07/does-santidevas-theory-make-demands/

I should also note that I generally don’t consider myself a Mahāyānist, in part because I do disagree with some of the universalist commitments recommended by that tradition – though I do think there is some overlap (as noted in the oxygen-mask post you cite).

This article presents a compelling argument about the role of obligation in moral philosophy. I appreciate the emphasis on balancing moral actions with personal well-being. The critique of guilt-driven morality resonates strongly, especially in today’s demanding social context. Your point about the importance of saying “you have done enough” is particularly vital for fostering self-respect and mental health. Thank you for this thought-provoking read!

Thank you, Charlie. I’m going to give you the benefit of the doubt and approve this comment here. I say this because your website address points to something called “vapedaddy”, which gives me the sneaking suspicion that this could be a spam post written by AI in order to look plausible. I hope that’s wrong; if it is, would you mind replying to this comment and saying so?