Tags

B.R. Ambedkar, caste, Elijah Muhammad, Four Noble Truths, identity, Maharashtra, Malcolm X, Nation of Islam, race, United States, upāyakauśalya, W.D. Fard Muhammad

It’s hard for me to view B.R. Ambedkar as a real Buddhist, when he threw out the Four Noble Truths after getting to Buddhism by a mere process of elimination. But then, to a real Buddhist, it shouldn’t matter – at least it shouldn’t matter much – whether you are a “real Buddhist”! Buddhism has no more essence, no more svabhāva, than anything else does. What really matters is relieving suffering. What’s more important than his status as a Buddhist is that Ambedkar’s rejection of the Four Noble Truths deeply inhibits the relief of suffering – or rather, it has the potential to. Yet things might be a bit more complicated than that.

I think a close analogue to Ambedkar Buddhism is the American Nation of Islam (NOI), whose most famous member was Malcolm X. The NOI arose in the early 20th century from black Americans, a group with status parallel to Ambedkar’s Dalits. Just like Ambedkar, the NOI’s founders W.D. Fard Muhammad and Elijah Muhammad rejected the dominant “religious” tradition – Christianity in the Muhammads’ American case, Hinduism in Ambedkar’s Indian – on the grounds that it was keeping their people down, and looked to replace it with another they deemed more suitable, Islam or Buddhism. And both Fard and Ambedkar took what might charitably be called a creative interpretation of the tradition in question, making it say whatever seemed convenient to them. Fard’s version of Islam, in particular, preached that white people were a race of devils created by a mad scientist – not exactly a view you’d find in the Qur’an or hadith.

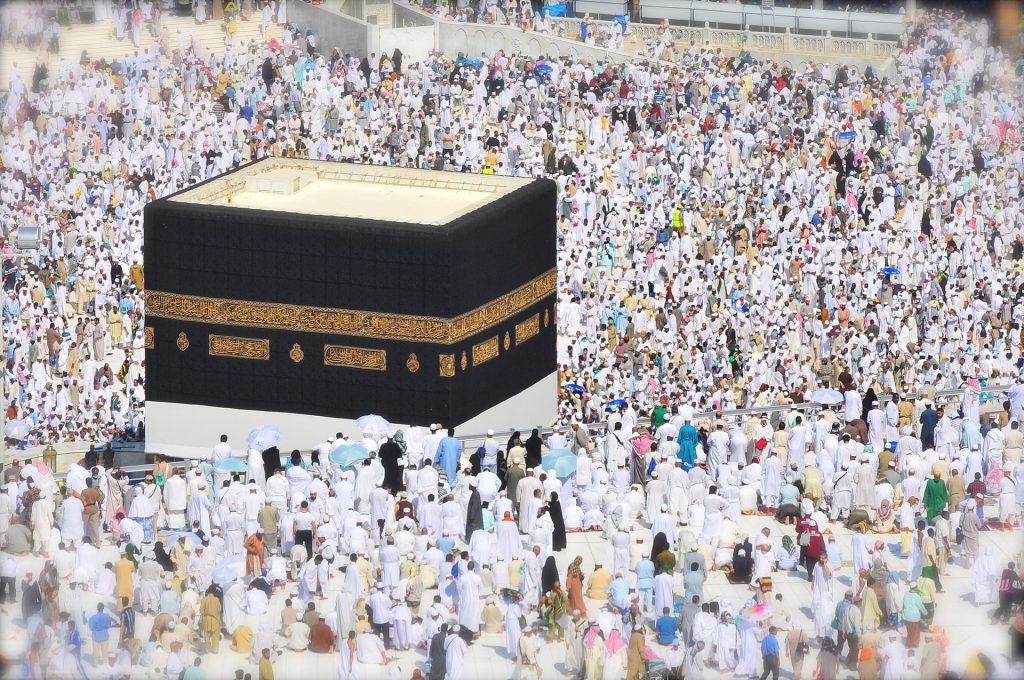

And yet over the course of the 20th century, something fascinating happened in the Nation of Islam. Most famously, in 1964 Malcolm X came to reject the Nation of Islam and make the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, traditionally required of all Muslims but not a part of NOI doctrine. X’s account of the hajj in his autobiography is quite moving. There, in Mecca, he saw something he had never seen in the US: a huge mass of people of all races, including both black and white, coming together as one for a common purpose. What X came to call “true Islam” proved far more inspiring to him than Fard’s doctrine of separatism and suspicion. And indeed, when Elijah Muhammad’s son Warith Deen Muhammad took over the NOI organization, he brought it more in line with traditional Islam, emphasizing the Five Pillars and converting NOI “temples” into traditional mosques.

Thus, while a traditional Muslim leader might quite reasonably have looked with alarm at Fard and Elijah Muhammad’s rather loose cultural appropriation of their faith, in the end it had the result of bringing new traditional Muslims into the fold. Give newcomers the space to do weird shit with your tradition, it turns out, and some of them will start to discover the real thing.

And it is ultimately from that perspective that I view Ambedkar’s Buddhism. Buddhists are fortunate to have easily available the doctrine of upāyakauśalya, skill in means, according to which the Buddha taught different teachings according to people’s level of development. I’m not aware of any Islamic equivalent of upāyakauśalya, but I think if I were a Muslim I’d feel like that was a great way to describe the original Nation of Islam: God addressing people who weren’t ready for the real thing, but finding a way to prepare them. And what Ambedkar did, exactly parallel to Fard and Elijah Muhammad, was create legions of people who considered themselves Buddhists. He increased the number of self-identified Buddhists in India from 181 000 in 1951, before his conversion, to 3.25 million afterward – a number that has only continued to grow. He single-handedly brought back something called Buddhism to its land of origin, where in the centuries before it had nearly died out. Even if we don’t count these new converts as “real Muslims” or “real Buddhists”, they are nevertheless legions of people who are primed to be real Muslims or Buddhists according to a stricter criterion. And that is worth celebrating.

Ambedkar Buddhism may be particularly well positioned to be a skillful means. In a society as suffused by egalitarian ideals as ours, for people as genuinely downtrodden as Dalits are, it may be much harder for them to see how suffering comes from craving. I was able to see that because, like Prince Siddhattha coming from the palace, I was in the position of seeing that having my cravings fulfilled didn’t stop the suffering. A Dalit probably can’t see that. It may be that the first and foremost thing for a Dalit is social uplift to get to the point where they can see that – which can surely involve means far more modest than mine have been, but may still require having food and health care in a way Dalits and their families often won’t. The great thing is, if the Dalits who rise into a middle-class-ish life are Ambedkarites, then their children may well be positioned to discover the content of traditional Buddhism for themselves – in a way they wouldn’t be if their parents were Muslims, Christians, or Marxists. That is a great thing.

I don’t feel great about Ambedkar coming to Buddhism through process of elimination, but I can’t be too hard on him for that. My own path to Buddhism first came through something similar: I was intrigued by it as a religion with no gods, drawn to it not for what it was but for what it wasn’t. The difference is that as far as I can tell, unlike Ambedkar, I let Buddhism change me. Before I found Buddhism, I assumed my suffering was because of bad life conditions; I had thought we had a duty of political activism; I thought anger was an appropriate response to injustice. In none of Ambedkar’s writings do I get any sense that Buddhism made any similar changes for him – that he ever encountered any Buddhist wisdom that taught him he should have done things any differently than he already was. But maybe that’s okay in the end, if it leads Ambedkar’s many disciples to discover Buddhism in a way that changes them.

Good posts. I think there are lots of reasons to be happy about Ambedkar Buddhism whatever its philosophical teachings …. You’ve identified one important one. But there are others. Buddhism is so much more helpful for Ambedkarites than Hinduism, for one. Buddhism is relied on, for example, for training young people in positive attitudes and conduct, and for having self-esteem. It has helped a genuinely oppressed group reduce their oppression–and even if the main causes of suffering are mental, creating a space outside of caste oppression has helped the minds and lives of those who converted. Removing “outer” sources of suffering is not nothing– that’s why engaged Buddhism exists. And seeing Ambedkarite Buddhists in recent years in Bodh Gaya, as I have, is cheering. When I saw them there in the 1990s, they were quite poor and their demeanor was … meek and downtrodden. Now they are a much more middle class community who have lost that struggling demeanor; I think that shows less internal sense of being downtrodden. They are proud in a good way, and show in their conduct that they are not “less than” any other Buddhist group. This is a mix of inner and outer accomplishment, and part of it is surely attributable to Buddhism, both its useful mental teachings and its disdain for the caste system and support to Ambedkarites to carve out a world outside that system, even to laugh at that system instead of being crushed by it…

Amod, some of the wording in this post sounds like you’re saying that Ambedkar’s Buddhism is upāya preparing people for, and pointing to, “real Buddhism”. Without denying that, what is funny about that wording to me is that I would say that so-called “real Buddhism” is also upāya preparing people for, and pointing to, a realization beyond real Buddhism. This is expressed in various ways in Zen, like Dōgen’s term “going beyond buddha” (butsu kōjō ji). The “real thing” turns out not to be the real thing…

There seems to be some tension between the statement in the previous post that “for people who take the tradition’s ideals seriously, those ideals have a content, and that content matters” and the statement in this post that “Buddhism has no more essence, no more svabhāva, than anything else does”. The former statement seems to align with the conception of Ambedkar’s Buddhism as upāya pointing to real Buddhism, and the latter statement seems to align with “real Buddhism” pointing beyond itself.