Tags

AAR, Charles Darwin, conferences, David McConeghy, Friedrich Nietzsche, H.P. Lovecraft, J.R.R. Tolkien, kitsch, Mike Mignola, skholiast (blogger), Speculative Realism, theodicy

A few years ago, Skholiast wrote a lovely post on the philosophical significance of J.R.R. Tolkien and H.P. Lovecraft, two early 20th-century writers who shaped the genres we now call fantasy and horror, respectively. I was reminded of it this year at an enjoyable AAR panel entitled “Cthulhu’s Many Tentacles”.

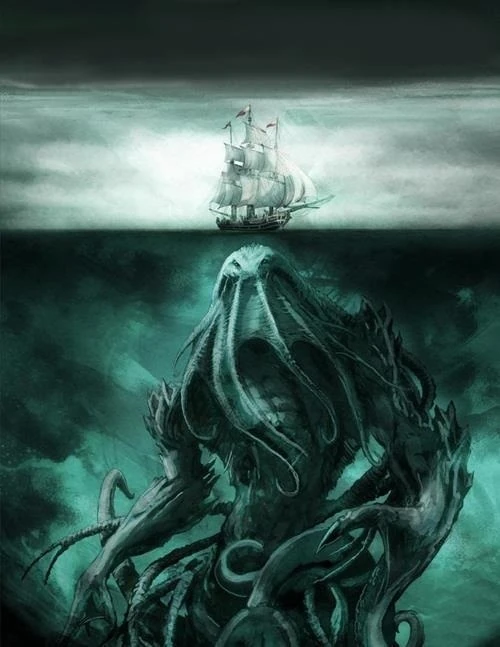

Cthulhu, of course, is the best-known character (if that is the word) from Lovecraft’s stories, enough that the fictional pantheon he created has become known as the “Cthulhu Mythos”. Cthulhu is one of a set of “Elder Gods”: horrifying, vaguely amorphous, often tentacled monstrosities that have lain dormant for millennia and will soon devour humanity; their horror is such that the mere knowledge of them could drive one mad. The AAR panel gave recognition to many aspects of Lovecraft’s work: starting with a presentation on the man and his work itself, the presenters proceeded to examine the varied dimensions of the fandom that has grown up around Lovecraft (noting, in particular, that fan creativity has been greatly enabled by Lovecraft’s work rising into the public domain).

Cthulhu, of course, is the best-known character (if that is the word) from Lovecraft’s stories, enough that the fictional pantheon he created has become known as the “Cthulhu Mythos”. Cthulhu is one of a set of “Elder Gods”: horrifying, vaguely amorphous, often tentacled monstrosities that have lain dormant for millennia and will soon devour humanity; their horror is such that the mere knowledge of them could drive one mad. The AAR panel gave recognition to many aspects of Lovecraft’s work: starting with a presentation on the man and his work itself, the presenters proceeded to examine the varied dimensions of the fandom that has grown up around Lovecraft (noting, in particular, that fan creativity has been greatly enabled by Lovecraft’s work rising into the public domain).

The most interesting point I took away from the panel came from a talk by David McConeghy (who also, coincidentally, was the respondent to my paper on teaching with technology). McConeghy noted that while a great deal of modern speculative fiction (he cited Mike Mignola’s comic-book series Hellboy) is clearly inspired by Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos and makes references to it, these works also typically have happy endings. The plucky band of heroes manages to banish the Elder Gods with their lives and sanity intact. Happy endings do exist in Lovecraft stories, but they’re rare. More commonly, the heroes go mad or are devoured, possibly on the way to the end of the world.

As I understand it, Lovecraft’s work is written this way for a reason. His was a time coming to grips with what Nietzsche – a major influence on Lovecraft – had called the death of God. Not so long before, it had been easy to think that everything in the world existed for the purposes of a divine creator who made human beings in his own image. It wasn’t just that this explanation helped make sense of metaphysics and ethics, it even was the best explanation of biology. After Darwin, this all changed drastically. God was no longer the most straightforward explanation for the diversity and functioning of life on Earth. For many he still survived as the source of value, but the physical world could be explained and explained well without him.

Meanwhile, as always, there remained a great deal that was harder to explain with God. Innocents suffer and die horribly every day, at the hands of humans and of nature; an omnipotent being that permits all this makes a sick joke of any claim to omnibenevolence. A world with God is now harder to make sense of than a world without him.

The important point, though, is that a world-without-God is not just a world-with-God with one entity subtracted from it. If we conclude that there is no God, then our understanding of the world around us must change drastically with it. It is that conclusion that was understood deeply by Nietzsche – and by Lovecraft.

One of the most familiar tropes from a Lovecraft story is the scholar who pores through dusty, long-forgotten books and discovers knowledge so horrible it drives him mad. (One of the panelists noted that Lovecraft’s parents were both committed to psychiatric hospitals.) There are dark secrets, things man was not meant to know. It is hard not to read this trope as an allegory for the scientists who discovered we could do without God. The idea of a world intelligently designed – still the most plausible biological hypothesis until Darwin – was a very comforting idea. It is a terrible and disturbing thing to learn that it is also a false idea. It turns out that the physical universe is a cold, dark, insentient place that does not care one whit about the insignificant accident that is the human race. It is easy to personify this universe as a collection of horrific, gargantuan monsters. For his part, Nietzsche, almost like a caricature of a Lovecraft character, spent the last ten years of his life unable to utter a coherent sentence.

As I understand it, this all is the appeal of Lovecraft to the Speculative Realist philosophers, many of whom are apparently quite fond of Lovecraft’s work. The key idea of Speculative Realism, as I understand it, is a decentring of human subjects from the prominent position they have been given by many modern philosophers (especially Kant). Lovecraft depicts this godless world, a world in which the human species is dust in the wind.

Skholiast, meanwhile, helpfully contrasts Lovecraft with J.R.R. Tolkien, an author similarly beloved by geek fandom. Tolkien, of course, remained a Christian through his life (like his good friend C.S. Lewis), and Skholiast remains a Christian to this day. And Skholiast emphasizes the importance to Tolkien of “eucatastrophe”: a reversal of fortune that brings about good results, because of the nature of the world. It is a natural result for a world genuinely created by an omnibenevolent God – which Tolkien’s Middle-earth was, just as he believed the real world to be.

It is essential to Tolkien’s writings, then, that they end happily. It is far stranger that contemporary “Lovecraftian” writings should do so. While such endings were not unheard of in Lovecraft’s own work, for them to be prevalent goes very much against the grain of Lovecraft’s own themes. If there’s an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God, then we can expect happy endings. But the world isn’t like that. Far too often real stories end not in eucatastrophe but in simple catastrophe, and Lovecraft aimed to reflect that.

The question that interests me is: why this change? Why do authors in our day feel a need to paper over even Lovecraftian fiction with a “Hollywood ending”? Part of it is surely just that many fans don’t take Lovecraft’s ideas seriously, not the way the Speculative Realists do. With his works in the public domain, they become icons of geeky popular culture usable for any purpose, including a wide variety of parodies.

But it does raise the question: why are we so devoted to happy endings, that we would write “Lovecraftian” stories where all is nevertheless resolved? I can imagine two answers. One is that happy endings offer us a pleasurable escape, of a form recognizable as kitsch. Alternately, though, it could be that we have never really adjusted to the idea that the world doesn’t care about us and that bad things are not part of a larger plan. As Nietzsche said, “God is dead; but given the way of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown.” Perhaps this is the literary manifestation of a theodicy instinct – the impulse that led Buddhists to answer the problem of suffering even though they don’t believe in a God?

Hi, Amod—

I attempted to answer this question at http://buddhism-for-vampires.com/lovecraft-harman-nihilism . In short, I think it is because we have adjusted to the idea that the world doesn’t care about us and that bad things are not part of a larger plan. This idea is no longer upsetting; it’s an unremarkable part of our everyday taken-for-granted understanding. That God died is funny, in retrospect.

I don’t think it is that simple. In your post you say: “However, nihilism shares the implicit assumption that the only real meanings are those that are rooted in an eternal ordering principle. Nihilism observes, accurately, that reality has no such principle. But then it concludes, idiotically, that there is no meaning at all.” But how idiotic is this, really? The existentialists wanted to think we make our own meaning, but they also granted a certain futility to that project, since so much of that meaning ends in death. It is notable to me that existentialism has fallen out of philosophical favour as Speculative Realism has risen.

Before existentialism, most people around the world found some sort of eternal ordering principle of this sort – such as the workings of karma. And even now, I think a great deal of atheists’ political activism is motivated by a desperate search for meaning in the universe – viewing ourselves as part of a titanic struggle toward inexorable progress. https://loveofallwisdom.com/blog/2009/10/neither-supernatural-nor-political/

I agree that existentialism is unworkable, and was abandoned for good reasons. Meaning is not subjective; that can’t work.

But there are other alternatives! Most of what I write tries to point out that meaning is real but not fixed/eternal/cosmic/objective. I think this is implicitly obvious to ordinary people, and is the way we all relate to meaning all the time. It’s only philosophers and theologians (amateur or professional) who get confused about this—which is why I call the confusion “idiotic.” It’s only bad metaphysics that obscures how meaning works.

I agree that this understanding is new-ish (it’s post-modern, so mostly since about 1980); ordinary people really did think people had fixed meanings before about then. I also agree that the New Atheists mainly set up atheism/scientism/rationalism as a new eternalism, which is mistaken and harmful.

How is an understanding that only existed since 1980 “implicitly obvious to ordinary people”? If it’s only ordinary people since 1980, which ordinary people are we talking about? The ones who get addicted to crack and heroin and meth? The ones who get clinical depression and commit suicide? These are not non-ordinary phenomena in the past few decades, nor are they more widespread among metaphysicians.

Hmm, I’m not sure what you are asking about addiction, or about depression? I don’t think people get addicted as a result of taking up a metaphysical position of nihilism—do you? Depression and nihilism are related—my impression is that either can lead to the other—but most depressed people are not nihilists.

Cultures can change, quite quickly; ours has. The changes in the way a culture construes meaning are taken up more readily by younger people, on the whole; my impression is that Millennials are much less likely to display either eternalism or nihilism than earlier generations. But I think the new understanding is implicitly available to many/most older people as well.

“It turns out that the physical universe is a cold, dark, insentient place that does not care one whit about the insignificant accident that is the human race.” Is that in fact, Amod, “the way it turns out,” or is that just the metaphysics underlying contemporary science speaking? How committed are you personally to that metaphysics being essentially correct? Is it possible that the existentially unflinching stance Nietzsche took staring into the void will eventually be seen as a somewhat quaint, quirky view that characterized the West from the mid-19th to mid-21st century, but nothing more? Is it possible that that view may be someday replaced by a view that perhaps takes telos and consciousness more seriously (e.g., like Nagel or Whitehead)? Just something I like to wonder about, mostly because the current dominant materialistic metaphysics happens to be very bad at making sense of and solving certain central philosophical problems. (Not that any specific other metaphysics is necessarily more successful.)

Well, I think that that is the way it turns out – but on theological as well as scientific grounds! I have noted this above: it is not just that God is a poor explanation of biological adaptation, but that fact combined with how his existence is so difficult to explain in the face of suffering. I certainly don’t endorse a materialistic metaphysics, but that doesn’t imply a God by any means.

How committed I am to this view is a good question, though. I am exploring the role that teleological explanation still plays in evolutionary biology and want to see what significance it might have. I do still find Aristotelian thought among the most powerful for explaining the world, and there is an odd kind of meaning that emerges there – though for Aristotle himself it is not as theistic as commentators from the Muslim Golden Age on have made it out to be.

Great post! I’m sorry I missed that AAR panel. Whether “Lovecraftian” stories have happy endings I suppose that depends on how strictly you define “Lovecraftian.” I’m currently reading a nice anthology of Lovecraftian fiction by women called She Walks in Shadows. I haven’t noticed any “happy” endings yet (although I suppose Lovecraft’s point would be that our notion of what counts as a “happy ending” is cosmically insignificant). But I do see your point about stories that merely have Lovecraftian influences rather than being actually part of the Cthulhu Mythos.

I imagine happy endings sell better and are more satisfying as a kind of wish fulfillment in a world that often lacks happy endings. Perhaps the continuing popularity of Lovecraft is that he gives a weird sort of comfort to those of us who have trouble seeing this as a universe of happy endings. I personally find Lovecraft’s vision of the universe more “believable” (whatever that means in this context) than, say, Tolkien’s (although I love Tolkien, too). On the other hand, I wonder if the Lovecraftian pantheon is itself a kind of comfort: at least we wouldn’t be alone in this vast uncaring cosmos. For more on this point and several others see a post on my blog called “Weird Knowledge: Lovecraft as Science Fiction and Philosophy” (http://examinedworlds.blogspot.com/2015/10/weird-knowledge-lovecraft-as-science.html).

When Christians consider the main differences between Christianity and Buddhism, they focus on the definition and existence of God. I don’t know enough about Nietsche, but certainly your post comes from this same perspective — it identifies the presence or absence of God as the central question. And, if you are right, Lovecraft seems to view the absence of God as having equal significance to a Christian’s faith in god.

Both of these (theism and atheism) are essentially Christian (and Western) views. And it is hard to conceive of what the alternative view might be. As Mipham the Great said: eternalism and nihilism are like the elephant that wades in the river to wash off the dust and then throws dust on his back to dry off the water. They are mutually dependent.

Buddhism doesn’t engage with the issue of the existence of God. It is simply not important. From a Buddhist perspective, the main difference between Christianity and Buddhism is the Christian belief in a self or soul.

The odd thing is that I think that there is a ground for Christian Buddhist dialogue using Christian terminology. It has to do with the Christian concept of God as being inconceivable, as “passing understanding” and the understanding that existence is rooted in concepts — to exist is to have qualities. Existence implies interdependence in the way that day does not exist without night. If God is inconceivable, God does not have qualities and is not defined as the opposite of evil. Evil is in no sense an opposite of or on a par with God. Evil is simply an aspect of being caught in a body, subject to the duality of good and bad. God is beyond this concept (which doesn’t mean God doesn’t exist or that God does — just that question of God’s existence / non-existence misses the point.

So sorry to be responding about a month late. Somehow I missed this post. Two brief observations:

I agree with Jim Wilton that the “existence of God” is usually thought of as the main cleavage plane between Buddhism and Christianity, whereas a deeper disjunction might be the existence of the self. I think it is at least arguable that Christianity also does not “believe in self”, though clearly it believes in “the soul,” in some fashion — the notion of some continuity after death. Obviously, however, many forms of Buddhism also maintain this. It is (to me at least) an open question whether Christian and Buddhist anthropology is compatible. I suspect the answer is yes, but that this compatibility may also depend upon a rehabilitation of the relevance of the question of God, too, because the person need not be thought of in terms of “self”.

As to the issue of the “Happy Ending,” I pretty much think that those narratives which try to construe Lovecraftian mythology in that direction are false to him — though there is some early precedent for it (August Derleth.) I attribute it mostly to Amod’s likely contender — a strong anthropological need for resolution and reassurance, which, yes, can be very kitschy, though I do not want to reduce it to that. In any case, my own concern with the rising fad of Lovecraftianism is with those who avowedly Do Not want to take this turn — in particular, writers like Ligotti and philosophers who have taken their inspiration from him. I treat this a bit in this post.

Although I am on the record as really, really admiring Chapman’s work, and I mention him in the above-linked post as well, I pretty strongly disagree with him on this. Yes, one can make a case that “nihilism is silly.” But I am unpersuaded that this case has become as widely accepted as he implies, and even if it had, it is far from obvious that this would be a good thing. I realize that I may sound portentous and all-too-serious in saying so, but it could just as easily be a sign of the increasing shallowness of our culture. Not every foe can be defeated just by being regarded as irrelevant or passé.